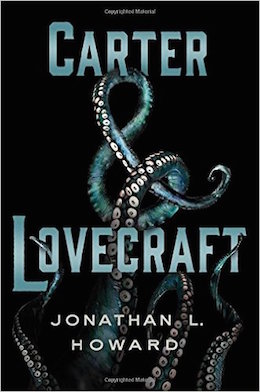

My seventh novel is titled Carter & Lovecraft and marks something of a departure for me in a variety of ways. Firstly, it is contemporary and fits into what you might call “Urban Fantasy.” Secondly, it’s a work-for-hire gig insofar as, while I get royalties (thank heavens), I don’t own the copyright. I’ve worked in the video games industry, so I’m quite used to not owning copyright on a project, but this is the first time I’ve written a novel like that. It’s a strange feeling, looking at the rights page in the book and not seeing my name there. Thirdly, the novel is set in a sort of shared fantasy world called “America.” You may have heard of it.

I was approached to write the book via the good offices of Peter Joseph, my editor at Thomas Dunne Books, and Brendan Deneen, who sorts out these new IP things for Macmillan. We had a three-way conference call that included an exchange that went something along these lines. We had talked about the idea behind what would become Carter & Lovecraft (indeed, I suggested that as the title right there and then), when Brendan said, “Your accent… you’re not American, are you?”

“No,” I admitted. “No, I’m not. I’m English”

“But you live in America?”

“Nope. Just outside Bristol in the West Country. Long John Silver territory.”

A pause.

“But you’ve visited the States, haven’t you?”

No, I have not. I am shamefully badly travelled when it comes to lands beyond Britain, and it pains me to admit it. I have no firsthand experience of the USA.

But, that wasn’t such a big problem as it might be. Several films have been made in America, and it turns out that they have television over there, too. By watching these films and television programmes, I distilled the essence of the American experience and realised that it largely consists of cowboys and gangsters living in an apartment block with a doorman called Carlton. Thus intellectually equipped, I was able to write a modern-day story set largely in New York and Providence with the assuredness of a man who has done his due diligence.

I may have done a tad more research than that.

In truth, it was not difficult to research. The Internet is a wonderful thing, and there’s quite a lot about America in it, really. You’d be surprised. I walked the streets of Red Hook and Providence in Google Street View (well, not so much walked as wafted along in strange, whooshing lurches). I read up on the bureaucracy of becoming a private investigator in the state of New York, concealed carry regulations, Federal crimes, political career paths, probate law. I read so many legal PDF files. So many. So… many… PDF… files…

I also had cause to reread a good pile of H.P. Lovecraft’s work, which is never a chore (the novel is Lovecraftian in nature; there’s a hint in the title and everything; ah, you can see it now, can’t you?), as well as researching the man himself, which was more of a chore. I’m not one to drag him though the decades and judge him as if he’s living in the here and now, which seems unreasonable and reductive. The man was a long way from having a simple personality.

But, he did come out with some loathsome statements that betoken a level of xenophobia vitriolic even by the standards of his own time, stating repeatedly both in his published works and private letters that non-whites were either shiftless or sinister. His opinion of Jews was also almost comical in its predictability, despite having good friends who happened to be Jewish. Oh, and being married to a Jew.

Then again, he was inconsistent even in his racism; more than one of his stories involves an exotic “other” who—despite being willfully exotic at every opportunity—is presented as smarter and wiser than the Caucasian characters. “The Horror in the Museum,” for example, is defeated not by the English protagonist, but by the efforts of a morally ambivalent individual of vaguely Middle Eastern origins who decides he’s had enough of Rhan-Tegoth’s shit. Lovecraft even seems to be inconsistent on how strongly he held such views; he is ragingly racist in the earlier part of his writing career, seems to mellow for a good while, and then turns really nasty again just before his death. But… he also told the American Nazis to stick it in their collective ear. In short, he is a difficult man to quantify, and it isn’t really the intention of this piece to attempt it. Nicole Cushing catches some of my own mixed feelings in her essay Lovecraft, Racism, and the “Man of His Time” Defense.

Thankfully, Carter & Lovecraft being set in the present day meant I didn’t have to deal with the man himself. He’s long dead and gone, but some of the echoes he left are the foundation of the plot.

Right, what was I talking about before that digression? Ah, yes: Americaland—Home of the Twinkie and the ten-gallon hat. There’s the vocabulary, of course. There are all the obvious things, like pavement/sidewalk, but there are also usages, which aren’t quite so obvious. For example, I never once mastered when to use “gotten.” It’s so utterly alien to me that I quickly decided to trust to Peter to handle that sort of thing. I also originally wrote the thing out in UK English simply because I tried switching on the US dictionary, but it was flagging so many misspellings that they distracted me from the prose. Instead, I decided I’d fix the lot in one go when putting together the first submission draft. When I did finally switch from the UK to US dictionary, the manuscript lit up like Blackpool Illuminations the Fourth of July (in fairness to myself, I was pretty good apropos cultural references). I became used to clicking ACCEPT CHANGE quite quickly.

Despite my best efforts, it was inevitable that a few errors slipped through, to be caught by a covey of trusty American readers. (Did you know that America is no longer part of the British Commonwealth? Apparently they declared independence in 1976 or thereabouts, thanks to Paul Revere saying, “I see no ships!” and some bloke called Robert Redglare . I thought the whole place was essentially still a county, much like Rutland.) Joking aside, pretty much any writer except the most egotistical will tell you all about the importance of having good editors, but when you’re dealing with a culture and idiom that is not your own, even if you think you’re pretty familiar with it, that importance is magnified still further.

It would be remiss if I failed to mention one other factor in the novel that is a novelty to me: swearing. There is a modicum of swearing in the Johannes Cabal novels, but next to none in my other ongoing series, the Russalka Chronicles and Goon Squad. The thing is, Carter & Lovecraft is set in the here and now and—I don’t know if you’ve noticed this—but people are terribly sweary. It’s all “flipping this,” and “bother that, you melonfarmer.” Thus, with tears pouring down my face, I had no choice but to sully the otherwise pristine world of literature. I am very, very sorry.

So, there it is, a brief tour behind the scenes of Carter & Lovecraft. I say “behind the scenes” figuratively here, but I should mention with, I hope, justifiable pride that Warner Brothers TV picked up the option with heartening alacrity. I must be doing something right. I suspect it was the scene with the Pilgrim Fathers and the monster trucks. Thank heavens for my impeccable research skills.

Jonathan L. Howard is an author (the Johannes Cabal and Russalka Chronicles series), game designer, scriptwriter, and a veteran of the computer games industry since the early 1990s. His latest novel, Carter & Lovecraft, is available October 20 from Thomas Dunne Books.